An estimated 39,500 individuals were infected with HIV in 2015. [1] HIV disproportionally affects economically disadvantaged individuals, among whom African Americans and Hispanics are over-represented, in part due to low rates of HIV testing. An estimated 14% of persons living with HIV are unaware of their status, [2] and approximately one-third of HIV-transmissions are linked with undiagnosed infections. [3] Nationally, heterosexual sex is the second most common route of HIV infection, [1] but heterosexuals are less likely to be tested for HIV compared to other risk groups such as men who have sex with men (MSM). [4]

CDUHR researchers have been working to determine the best way to detect undiagnosed HIV infections among heterosexuals considered at high-risk for HIV because they reside in urban areas with high rates of poverty and prevalent HIV infection, called a “high-risk area.” Heterosexuals comprise 24% of newly reported HIV infections in the United States, but experience complex multilevel barriers to HIV testing, including stigma and substance use. Thus locating heterosexuals with undiagnosed HIV infection is difficult.

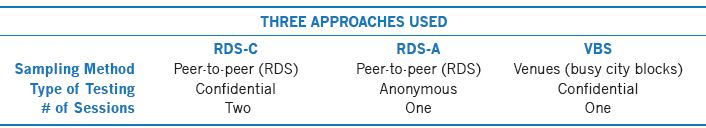

Gwadz et al. evaluated the efficacy of three community-based approaches for uncovering undiagnosed HIV and providing linkage to HIV care among heterosexuals at high-risk, who are mainly African American/Black and Hispanic. [5]

Each of the three approaches had unique features, as well as strengths and drawbacks, and the approaches were designed to be culturally salient and acceptable to substance users. All three approaches focused on those residing in a high-risk area in central Brooklyn. Respondent-driven sampling (RDS) is a peer-to-peer recruitment method that starts with recruitment of “initial seeds” who recruit a limited number of their peers, who then enroll in the study. Peers are recruited until sample size goals are met. In this way, we can reach individuals who may be more easily missed, in part because they do not commonly present to, or even actively avoid, organizational settings. Venues for the VBS were defined as a city block with >70% commercial activity (i.e., a busy city block) within the high-risk areas. VBS involved going to these venues on randomly selected days and at randomly selected times. Recruitment of “initial seeds” starting the RDS peer recruitment chains and VBS venues were located in this same high-risk area.

The investigators found that RDS-A reached a higher proportion of individuals with more risk factors for HIV infection and who were less likely to have been tested for HIV on a regular, annual basis as compared to the other approaches. Additionally, RDS-A (4.0%) and RDS-C (1.0%) testing yielded significantly higher rates of newly diagnosed HIV than VBS (0.3%).

Cost-effectiveness analyses demonstrated that all three strategies were cost-effective compared to no intervention when implemented either for one year or continuously. However, RDS-A with continuous implementation is likely to be the most effective and also cost saving.

Existing programs for identifying people with HIV, mainly those in medical settings, work well and capture most of those infected with HIV. Gwadz et al. focused on developing approaches to reach those who may not engage regularly with those settings, or who need encouragement to test for HIV. These individuals, many of whom do not test regularly for HIV, therefore require innovative, culturally appropriate HIV testing interventions. RDS and anonymous HIV testing in one session provide the most successful route for identifying HIV infection in difficult-to-reach heterosexuals at high risk for HIV, and can be combined with linkage to HIV care to maximize public health benefit.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016) HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html, accessed 09/04/2017.

- Hall HI, An Q, Tang T, Song R, Chen M, Green T, Kang J; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2015) Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV infection—United States, 2008-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 64(24):657-62.

- Skarbinski J, Rosenberg E, Paz-Bailey G, Hall HI, Rose CE, Viall AH, Fagan JL, Lansky A, Mermin JH. (2015) Human immunodeficiency virus transmission at each step of the care continuum in the United States. JAMA Intern Med, 175(4):588-96.

- Linley L, An Q, Song R, Valverde E, Oster AM, Qian X, Hernandez AL. (2016) HIV testing experience before HIV diagnosis among men who have sex with men—21 jurisdictions, United States, 2007-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65(37):999-1003.

- Gwadz M, Cleland CM, Perlman DC, Hagan H, Jenness SM, Leonard NR, Ritchie AS, Kutnick A. (2017) Public health benefit of peer-referral strategies for detecting undiagnosed HIV infection among high-risk heterosexuals in New York City. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 74(5):499-507.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA032083, PI: Gwadz; P30DA011041, PIs: Deren & Hagan).